LOVE CHILD

“… What justifies more than all / the dream, the great despair / the knowledge that there is no justification / and perpetually searching for it / the awe and distress, / that which justifies more than anything, / which justifies the great despair / is the simple, conclusive fact, / that in fact we have no place to go to…" (David Avidan)

Having served as a principal object of courting and admiration for the second half of the 20th century, “youth” is the great neglected of recent years. The advantages of youth have been stolen for the sake of the new class of the “young”, which is extended without limit, until the body does not afford us liberty any longer. The status of youth has grown weak as an economic power. It lacks behind the status of children – who are more loved, more endeared, the new extortionists of money and blame, and also behind the economic power of the adult bourgeoisie. The youth have nothing to offer: they have neither hope nor wallet; they are after sexual discovery and before uncovered sexuality. We have taken away from the youth all that they had, and now they are our martyrs, expressing with their own bodies the boredom, the cruelty, the confining spaces of the 21st century. The youth of Pitchon crash on the cement of the shopping center.

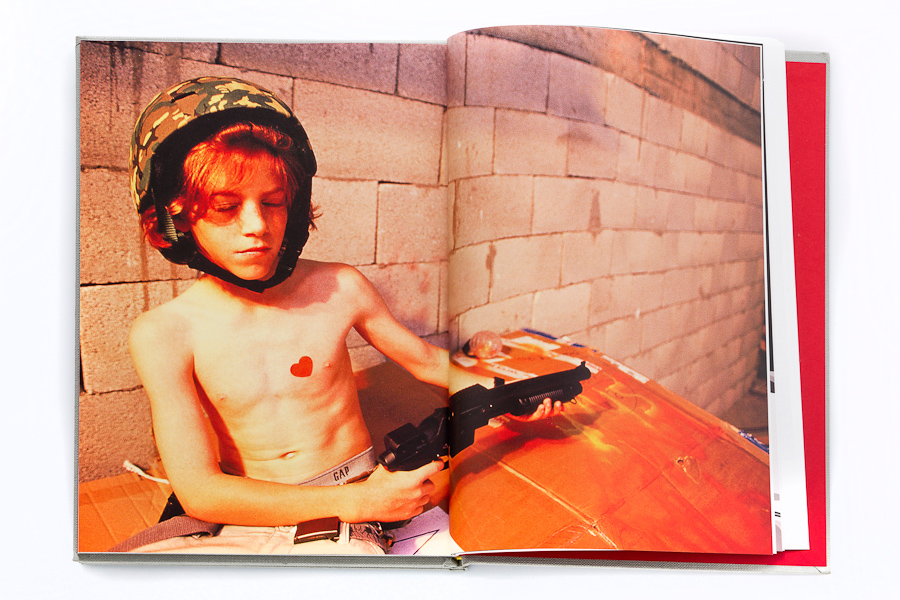

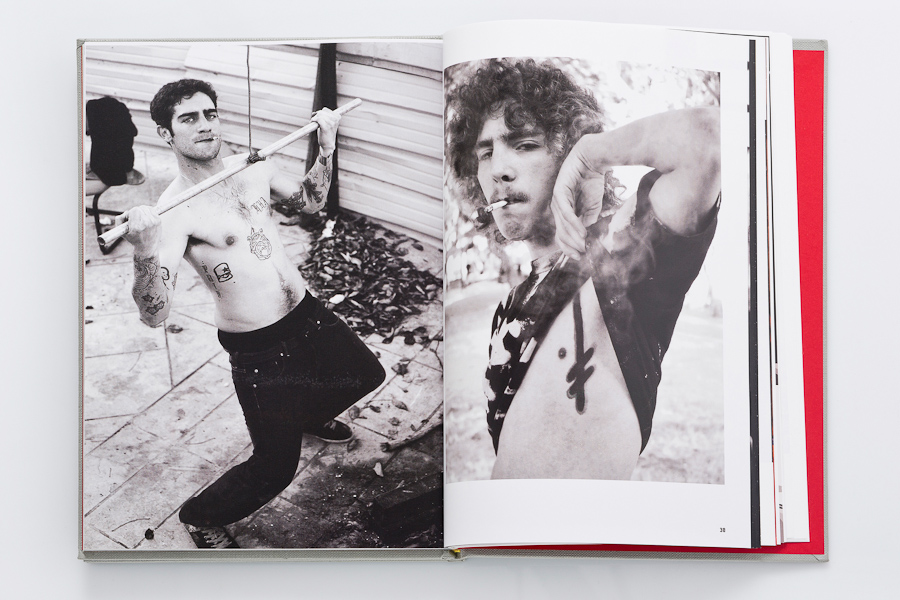

Literally translated, “love child” seems an ironic title to an exhibition that displays children or youth that at least seem to suffer from some lack of love or care. Correctly translated – "lovechild" is “bastard”, and in its figurative colloquial sense there is suitability: here they are, those little bastards. The title, like some of the works in the exhibition, belongs to tattoo clichés: Mother, Love Child, images of the Holy Virgin. The surprising incorporation of Christian motives in the exhibition seems at first sight as trashy pop, but the plea for mercy on the “children” is simultaneously genuine and deriding. It appears as though Pitchon presents a closed and hopeless world, in which all laws are clear, where money rules, the architecture serves as a system of control (echoing "free masons” conspiracy theories) and the only way to manifest an “I” is to engrave on your own body or otherwise harm it. However, Pitchon allows himself and the love children – are they anything but a collection of images of himself? – the right to pray.

The work “…refuse… resist…” summarizes the subject matter well: The silver pyramid with Big Brother's Cyclops eye is ruling from above. Underneath a nailed cross, the skater, in his usual uniform, sits again on the same pyramid – now one that can be used as a slide – and is occupied in what is seen to be a meek and passive prayer. The call: “refuse, resist” is surrounded, in the stammered language of text messaging, by endless dots that weaken it from all sides, rendering it ironic.

Pitchon's love children's oblivion is much more dim and limp than Larry Clark's, for example: instead of heroin there is Goldstar, instead of syringes – an improvised bong; the guns are toy guns, they cannot kill you. The absence of shock enables the situation to persist: there is no sex, there is no death, there is limbo. To return to Avidan: “The title 'young' is nothing more than labeling an intermediate state in a very long waiting room”.

As someone who has been moving for several years between commercial and artistic photography, between art and pop, between primitive engraving in wood and glass and digital photography, between the street and the establishment, between the adults and the teenagers, Pitchon himself is a Love Child, a bastard in the world of art. Let us pray for him.